Sketches of Teruya Ar(t)chive

2020

The Koza Jujiro Ichiba

(Koza Crossroad Market)

Teruya 1965

Courtesy of Okinawa City Archive

As merchants and “hustlers,” people created a new form of economy in Teruya, not only surviving the aftermath of the war but thriving under American occupation. Opportunities opened up and foreigners were recruited as labor for the constructions of new American military bases on Okinawa, arriving from places like the Philippines, Peru, Korea, Vietnam, Taiwan, and India. Koza Crossroad Market offered a panoply of life’s pleasures and possibilities: sundry of merchandise, eateries, movie theatres, futon shops, mom-and-pop stores, food shops, shoe shops, pawnshops, clothing stores, barbershops, beauty shops, tailor shops, record shops, cafés, billiards, hardware stores, midwifery, and small ad hoc entrepreneurial services (such as shoe shining, ice-cream, chewing gums, the making and selling of ice cakes and the sale of cups of Coca-Cola mixed with Okinawan Awamori). Shoppers from the southern to northern ends of the island traveled on busses to shop and hang out at the crossroad, which quickly became a social epicenter. Resisting the dystopia of war and American military occupation, people took control of rebuilding their lives in this place and created a postwar economic miracle. The world flags in the photos represent the multicultural and multiracial atmosphere of the place.

Honmachi Block Party

Teruya 1970

Courtesy of Kumi Matsumura

Honmachi Street was a thriving shopping center in the Teruya district that included a market district called Koza Jujiro Ichiba (Koza Crossroad Market) located at Koza Crossroad. The southside of Honmachi was an area known as the Black District, a bar and entertainment district serving black servicemen. This photograph shows people gathered at a block party, challenging the then held assumption of this place as being scary, black, and sexual. Block parties often took place on the Black District side of the Honmachi Street. However, prejudice often undermined the everyday lives of those who created and lived during this miraculous age of the district.

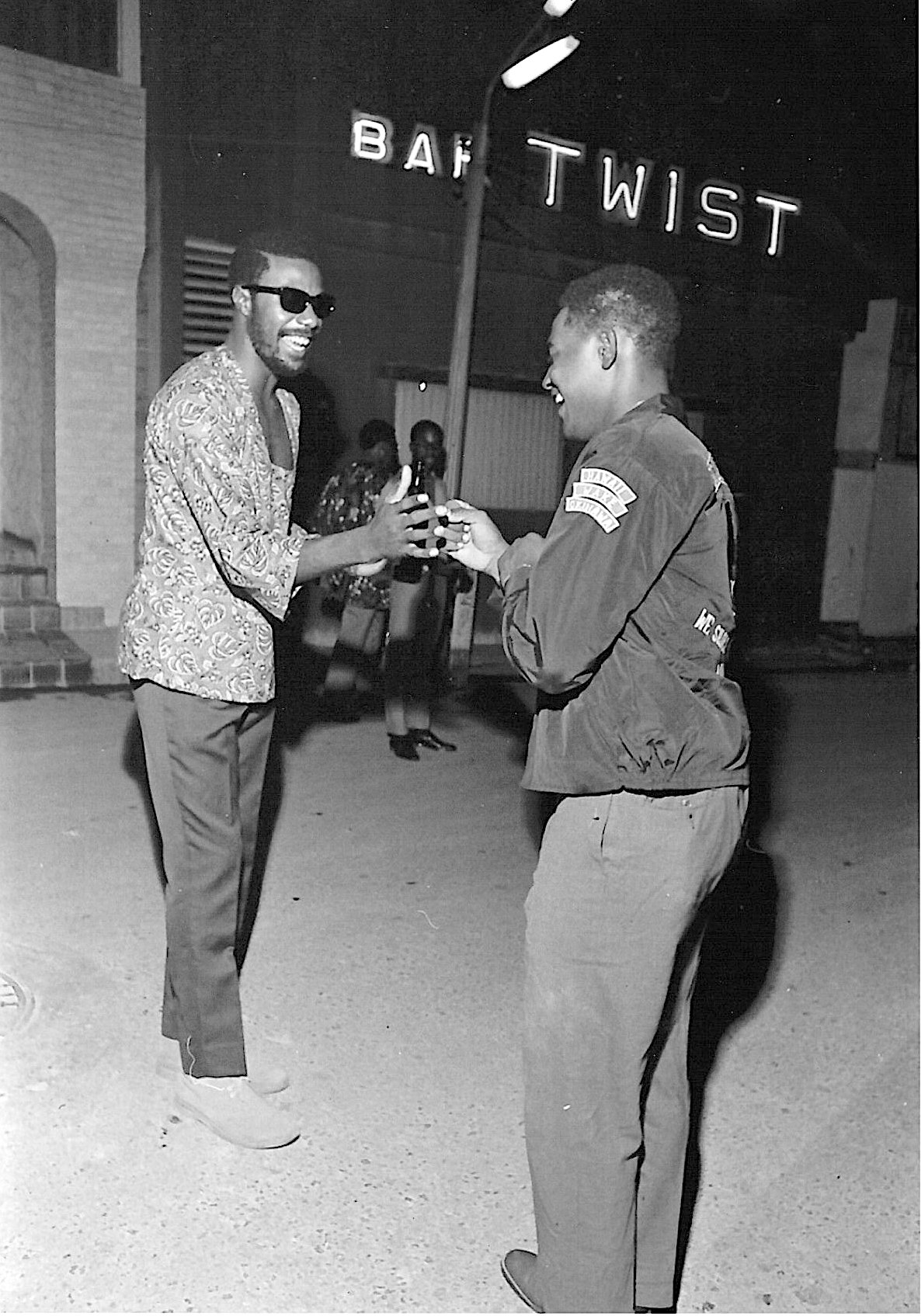

Bar Twist

Teruya 1970

Courtesy of Kumi Matsumura

Zen’s mother owned and operated a bar called the Bar Twist. The bar is on the first floor and the family lives on the second floor. Such mixed-use buildings were commonly seen in bar districts. Looking down from the window of his second-floor living quarter, Zen witnessed more than what most children his age are privy to. He saw a hostess getting dressed for her shift and watched two hostesses fight over a male customer. They pulled hair and ripped clothes. The fight he recalled happened in the early part of the day before the bar opened. Onlookers egged on the women, making a scene. After the fight, the place became quiet for a while, and right before the bar opened, he watched as the women who earlier were rivals now acted like buddies cleaning up their mess as they readied for work that night. For Zen, the place became a movie set with “lights, camera, and action” as soon as he saw a group of black men dancing, singing, talking, giving hi-fives, and raising the iconic fist of black power. They taught him how to give hi-fives and carried him high in the sky as he and friends playfully communicated with the black men using fake “Engrish,” rhythmically and nonsensically sounding off what they heard. Payday was especially lively when businesses in all three areas bustled with people, selling and buying, eating and laughing, dancing and singing in the streets.

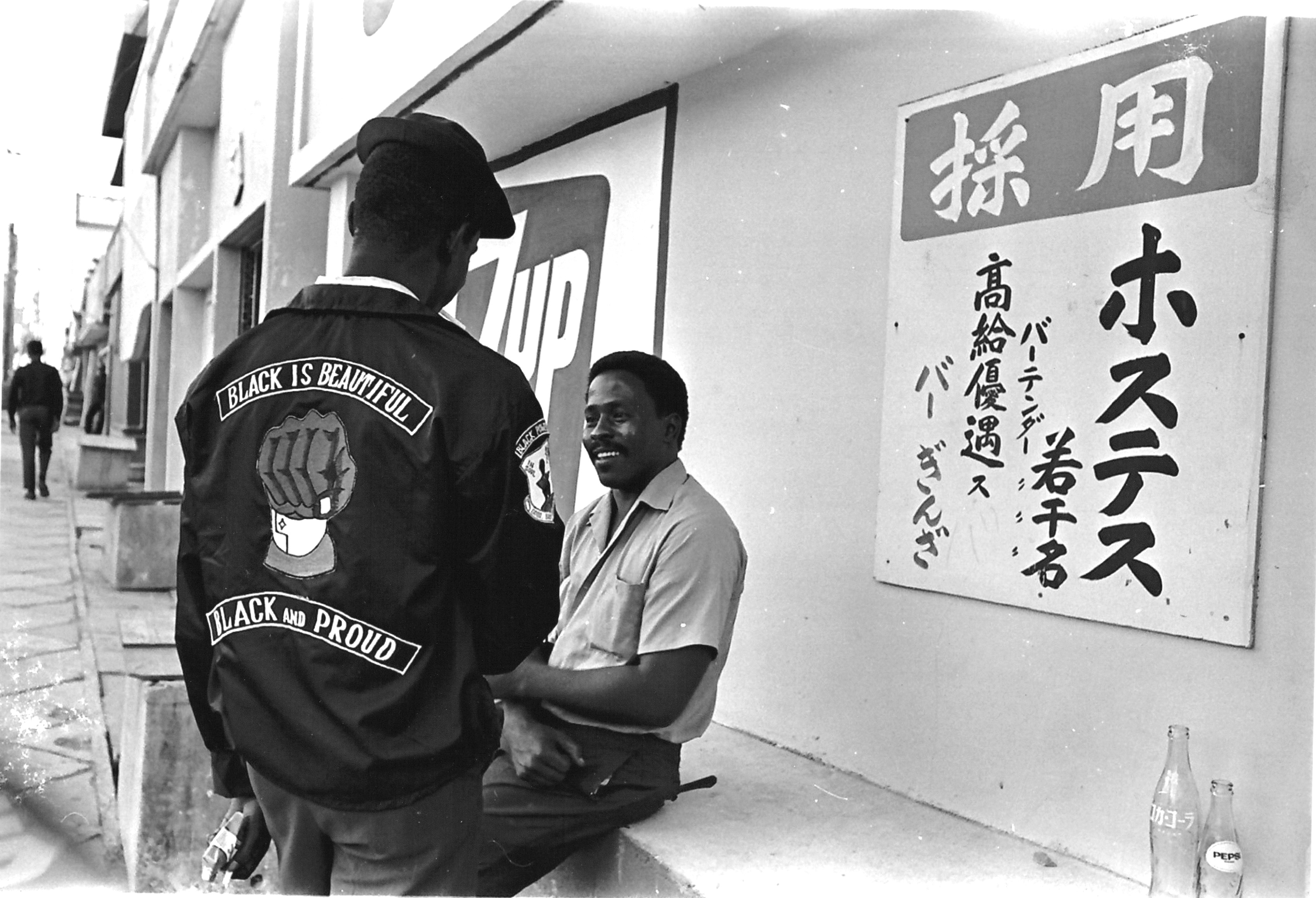

Barbershop

Teruya 1975

Courtesy of Kumi Matsumura

The Black District was a district located in the Teruya’s market district called the Honmachi-dori. Nestled within the market, the Black District existed from 1953 to 1976, operating beyond the formal occupation period that ended in 1972. Located in the northwest of the seaport, the district was also called Four Corners, where the dramas of everyday life unfolded against the backdrop of the US military occupation, the black international radical movement, the military sexual economy of the bar and entertainment districts, and the everyday life and hustle of Okinawa. As the photograph shows, the relationship between Okinawan business people and black servicemen went beyond monetary exchanges.

Bar Ginza

Teruya 1970

Courtesy of Okinawa City Archive

The photograph shows two black men sitting in front of Bar Ginza located on the southwestern side of Koza Crossroad (Route 24), Bar Ginza was one of the bars frequented by the members of Bushmaster, a radical activist group. Route 24 connected Kadena Air Force base to Awase seaport. Bars and other businesses lined the streets of the route. The Black District was not only limited to the street on Honmachi or main streets but also spread into the residential areas where bars and hotels were intermixed with other businesses.

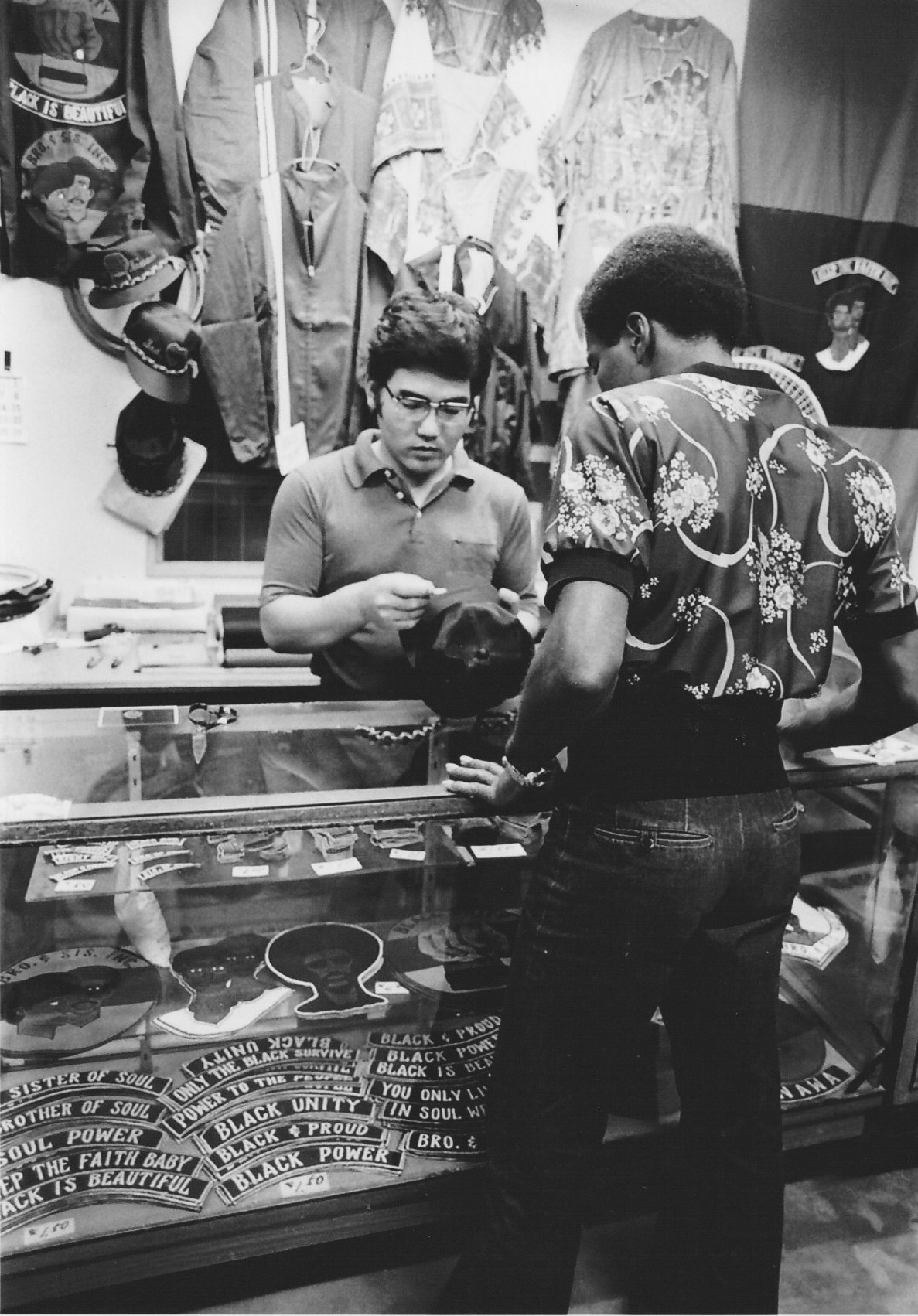

Embroidery Shop

Teruya 1975

Courtesy of Okinawa City Archive

Teruya’s Black District existed from 1952 to 1976, a period marked by the emergence of the Black Civil Rights Movement, the Black Panther Party, Malcolm X, and the anti-Vietnam Movement. The Bushmaster, one of many groups that operated in the district, fought against western imperialism through the efforts of the black international movement. Teruya was a haven for black soldiers who experienced racism in the military, the very institution that oppressed their humanity. Black soldiers made Teruya their “home,” naming the crossroad, the “Four Corners,” a place of refuge for black individuals. During this period of black radicalism, phrases such as “Black is Beautiful” and “Black Power” were birthed and radicalized the world. They debunked the myth of blackness as a negative attribute and simultaneously claimed the right of being a human for all around the world. Tailors and embroidery shops like the one shown in the photograph played an important role in offering the material (patches, cloth etc.) that would be used to represent the desire of black people who sought a different black life and black futurity. We might call them the retrospective equivalent of BlackLivesMatter.